By Eric Karsten, Chong An Ong, Immanuel Adriana Rakshana, and Arushi Saksena, University of Chicago

The minimum wage is a contentious issue, with proponents arguing that it is required to protect the wage security of low-income earners, and opponents arguing that it places downwards pressure on employment in the labor market. Our paper uses a differences in differences regression model, similar to the one used in Card & Krueger(1993) to estimate the unemployment effects of a minimum wage increase. Based on the four minimum wage changes used, we do not find convincing evidence that changes in the minimum wage lead to changes in unemployment levels. This contradicts the standard economic theory that a price floor in the labor market will lead to unemployment.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we explore whether, and to what extent, increasing the minimum wage has an effect on employment. To do this, we look at the following state combinations in the United States: Kentucky and Tennessee, Oregon and Washington, Michigan and Ohio, and Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We chose these state combinations based on similarities in variables like income, age, welfare, so that our matched pairs design can most powerfully isolate the effects of the minimum wage change. We then selected a year in which only one state in each pair increased its minimum wage, while the other maintained its initial minimum wage.

The minimum wage changes we examine are:

- Kentucky: Changed minimum wage from $6.55 to $7.25 in 2010; Tennessee: Kept minimum wage the same from 2009 to 2010.

- Washington: Changed minimum wage from $6.50 to $6.72 in 2001; Oregon: Oregon kept minimum wage the same from 2000 to 2001.

- Ohio: Changed minimum wage from $7.95 to $8.10 in 2015; Michigan: Michigan kept minimum wage the same from 2014 to 2015.

- New Jersey: Changed minimum wage from $7.25 to $8.25 in 2014; Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania kept minimum wage the same from 2013 to 2014.

In general, our findings show that minimum wage increases did not lead to dramatic reductions in either youth or general unemployment. These results are discussed later in the paper.

2. Literature Review

In recent articles, the NYT Editorial Board and prominent economists such as Alan Krueger and Paul Krugman have come out in support of raising the minimum wage (Krueger 2015)(Editorial Board 2014). The empirical evidence, both in the United States and internationally, suggest that contrary to conventional economic theory, raising the minimum wage does not exacerbate unemployment. Obviously, there will be some point where this will no longer be true, but research suggests that that threshold may be higher than the minimum wage raises being discussed as policy options today. These pro-minimum wage economists suggest that a higher minimum wage could help employers fill vacancies and keep turnover low and may be necessary to keep pace with inflation and productivity growth.

That said, there is no consensus among economists on this topic. Christina Romer, former Chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers counters that the minimum wage is a blunt policy tool. Education subsidies or tax credits such as the EITC, which are specifically targeted at the poor, tend to be more effective (Romer 2013). She also suggests that ultimately, employment at any wage is preferable to unemployment as a tool for lifting workers from poverty. Romer acknowledges though that raising the minimum wage serves as a direct means of boosting the bargaining power and wages of low-wage workers – so raising the minimum wage would be better than nothing, but worse than many other policy solutions.

Turning from editorials to academic papers, we consider Card and Krueger’s seminal study in 1994 on a minimum wage change in New Jersey. This was the first study that contradicted economic theory, finding that raising the minimum wage didn’t put measurable downwards pressure on employment. They compared fast food restaurants in New Jersey, where the minimum wage increased from $4.25 to $5.05, to those in Pennsylvania, a similar environment where the minimum wage remained constant. This controlled differences-in-differences natural experiment found no direct correlation between raising the wage and workers being laid off in an industry filled with minimum wage workers (Card and Krueger 1993).

In a more recent paper, Harasztosi and Lindner discuss the impacts of a roughly 60% minimum wage increase in Hungary in 2001. They use two major data sources: the Hungarian National Wage Survey and the Corporate Income Tax Data, making their study more comprehensive than those in other survey settings. Harasztosi and Lindner concluded that the increased minimum wage had a minor negative effect on employment, and did not reduce the profitability of low-wage employers; most of the costs of the wage increase were passed directly on to consumers through increased prices (Harasztosi and Lindner 2015).

Giuliano uses data from a large US retail firm to study the 1996 federal minimum wage increase. She found that the negative impacts on employment from this change were statistically insignificant.She did however find that there was an increase in the employment of teenagers, suggesting that the wage increase to some extent took jobs away from older workers who needed them more (Giuliano 2013).

In a review by Betsey and Dunson of minimum wage studies, the authors conclude that such research often overstates the impact of the minimum wage on reductions in employment. They suggest that cyclical factors have effects of greater magnitude than the effects of the minimum wage change (Betsey and Dunson 1981). Our study specifically addresses this issue using a differences in differences approach that (to a first order approximation) removes these cyclical effects from the wage changes we observe.

Allegretto and Reich use a dataset of online restaurant menus in the San Jose area to show that a 2013 increase in the minimum wage by 25% led to an increase in prices by about 1.45% (Allegretto and Reich 2018). This is consistent with the theory that raising the minimum wage in general doesn’t lead to reductions in unemployment because labor demand tends to be quite inelastic. Instead, these wage increases are passed along to the consumer.

3. Economic Theory

The standard model of minimum wage used in economic theory is a price floor model of supply and demand. This model represents a simple equilibrium where demand meets supply, and then shows the effect of a minimum wage (price floor) on the equilibrium in this model.Here, introducing (or increasing) the minimum wage increases the cost of hiring workers to firms, and also make working more attractive to labor. This decreases labor demand and increases labor supply, creating an excess supply of labor in the market, commonly known as unemployment.

Our findings favor an alternative model where labor demand is highly inelastic, but prices are fairly elastic. This is plausible because in the short run it is difficult for firms to substitute away from labor. In this model, the profit-maximizing firm sees two effects at once:

- An increase in the willingness to pay of consumers due to higher incomes.

- An increase in cost of goods sold due to higher prices of labor inputs.

The natural result will be a similar equilibrium level of labor and a higher equilibrium price. In the labor market, our results are similar to those in Card and Krueger (1993): increasing the minimum wage does not lead to significant changes in unemployment.

4. Methodology

Our paper has three main sections: We first test the extent to which matched state pairs are actually similar. In particular, we want to check to see if our chosen state pairs are similar enough to be used in our difference in differences model later on in the paper. We do so by first observing some summary statistics of key variables (income, age, welfare, proportion of the population that is white, proportion of the population that is male, proportion below the poverty line, and proportion with tertiary education). We then conduct t-tests to empirically test if the two states are in fact similar. This allows us to minimize the extent to which differences in other factors (like differences in the types of jobs people are working in each state) are viable explanations for unemployment changes in one state compared to another.

In the second section, we graph the unemployment rate over time for each state, and insert vertical lines at the locations of minimum wage increases to look at time trends. While it is difficult to parse differences between the states visually, we do note that there is no strong indication that increases in the minimum wage have ever led to increases in the unemployment rate (visually netting out trends across the united states).

Finally, we run regressions using difference-in-differences with state pairs and year pairs as comparison groups. We use the dependent variables of youth and total workforce unemployment. In these regressions, we control for potential confounding factors including race, education, sex, and English proficiency.

5. Data

We use a combination of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and from the American Consumer Survey (ACS) provided by the U.S. Census Bureau. State and month level data on unemployment is taken the BLS, and used to calculate means and create the graphs of unemployment over time.

Individual-level data taken from the ACS is used to calculate population means for the other variables (average income, average age, average welfare, percent male, percent white, percent with some tertiary education, average welfare received, percent below poverty line), as well as to run the regressions on youth and full unemployment. We consider youths to be all those between 16 and 24 years of age (the standard age range used by the BLS to define youth unemployment). The ACS data is collected via surveys of randomly selected addresses. The responses are then weighted to be a representative sample of the US population and we use these weights in our regression estimation.

The regression is run on state and year interactions, and controls for race, education, sex, and whether or not the individual speaks English. It is worth noting here that we are using a somewhat unusual measure of employment rate. We measure the proportion of people eligible to work who are working, not the proportion of people who have a job or are looking for a job who are working. This was done in order to capture the effects of wages moving people into the labor force.

6. Comparing States

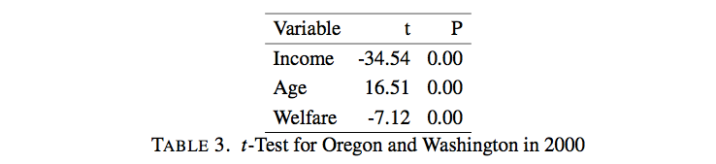

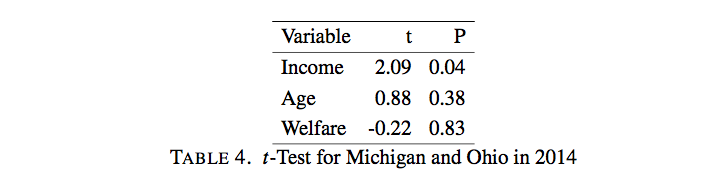

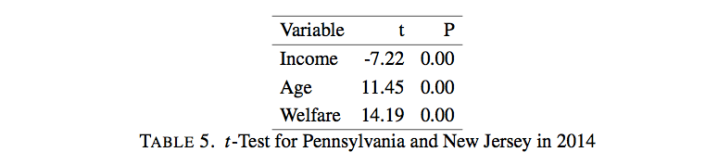

We find from table 1 that broadly speaking the state pairs are similar across a wide variety of summary statistics that could have relevant effects on the unemployment response to a minimum wage change. That being said, we want these observations to be more robust, so we conduct t-tests to see how similar our pairs of states really are. Our t-tests seek to show that we cannot confidently find a significant difference between our state pairs, so a failure to reject our null hypothesis (that the means of two populations are the same) is a good sign. Our results for the differences-in-differences methodology will be more robust if our state pairs before the minimum wage changes are not statistically different. Therefore we want to fail to reject the null, that is get a p-value greater than .05. We use a standard t statistic given below with pooled standard deviation Sp and Welch’s correction for degrees of freedom.

6.1. Kentucky and Tennessee

The minimum wage change we will be studying is the 2010 wage change in Kentucky (from $6.55 to $7.25). We will be therefore be comparing Kentucky in 2009 to Tennessee in 2009 to see if they are similar. Our t-test output is in table 2 . Since our p- values for age and welfare are above 0.05, there is not a statistical difference between these two variables, and we can hence infer that Kentucky and Tennessee are similar states according to the methodology defined above. However, we find that there is a statistical difference between the states in total family income.

6.2. Oregon and Washington

We are looking at the minimum wage change in Washington State in 2001 (from $6.50 to $6.72). We are therefore comparing Oregon and Washington in 2000 to determine whether they are similar. Our t-test output is in table 3. We generally find very significant differences across all our other variables, indicating that we should proceed with caution in drawing conclusions from differences in unemployment in Oregon and Washington. We mitigate this to some extent by controlling for these differences between the states in our regression specification.

6.3. Michigan and Ohio

Ohio increased its minimum wage from $7.95 in 2014 to $8.10 in 2015 while Michigan’s minimum wage held steady at $8.15. We will therefore compare these states in 2014 to determine the extent to which they are similar. Our t-test output is displayed in table 4. We again find no statistical differences in either age or welfare, so we can infer that Michigan and Ohio are similar states in these senses. There is likely some statistical difference between the states in total family income though which our differences in differences specifically accounts for.

6.4. Pennsylvania and New Jersey

We are looking at the minimum wage change in New Jersey in 2014 (from $7.25 to $8.25). We are therefore comparing New Jersey and Pennsylvania in 2013 and 2014 to determine whether they are similar. Our t-test output is in table 5. We find very significant differences across all three of our variables. This indicates that we should be hesitant about drawing conclusions from differences in unemployment in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

7. Time Series Employment Charts

With Min Wage Shading

Before diving into our differences in differences regressions, we produce side-by-side plots of unemployment over time in each state that we will consider from January 1970 to March 2017. We add vertical bars to indicate the years in which the minimum wage was raised in each state, and then observe how those changes affect the plots of unemployment over time. This allows us to get a more general, visual idea of how minimum wage changes affected unemployment. All of these figures can be found in Appendix B.

7.1. Kentucky and Tennessee

We notice in Kentucky and Tennessee, changes in the minimum wage were followed by periods of both higher and lower unemployment. Figure 1 does not immediately point to any consistent trends that could reflect obvious effects of minimum wage changes of greater magnitudes than the cyclical changes in unemployment due to business cycle fluctuations.

When the minimum wage was increased in the 1980s, both states reflected a spike in the unemployment rate, and when only Kentucky introduced a minimum wage change in 2000 (our year of interest in the regression in the next section), Tennessee marked changes in its unemployment rate that were similar to those seen in Kentucky. This implies that the unemployment rate must have increased in this time period for other reasons, and that the minimum wage change in Kentucky did not significantly impact its general unemployment rate. We confirm this later with our regression analysis.

7.2. Oregon and Washington

The frequency of minimum wage changes in Oregon and Washington is the first, immediate difference from Kentucky and Tennessee–especially in later years.

We notice in figure 2 that prior to 2010, minimum wage hikes were followed by periods of increased unemployment. After 2010, wage hikes were followed by decreases in unemployment. In the 1980s, only Oregon changed its minimum wage, but both states experienced a spike in unemployment rate (albeit, to different degrees). In 2001, our year of interest, a regression will be interesting to run especially because of how many minimum wage changes were introduced after this year in both states.

What is especially interesting here is that there are spikes in unemployment for both the states after 2001, but the slopes of these spikes are different. For Oregon, there is a steeper increase in unemployment from 2001 to 2002, but in Washington (where the minimum wage changed in 2001), the rise in unemployment is flatter (but still exists) from 2001 to 2002.

7.3. Michigan and Ohio

Michigan’s minimum wage changes are concentrated on both ends, but Ohio’s minimum wage changes are concentrated in later years. This makes studying the unemployment changes noteworthy to consider because many changes are stacked together before 1980 for Michigan, and similar changes do not exist at all for these years in Ohio (see figure 3).

Regardless of this interesting disparity in minimum wage changes in the two states, both show similar trends in unemployment rates before 1980. Indeed, even in later years, there is no obvious visual difference in the unemployment rate over time regardless of whether or not there was a minimum wage change in one state and not in the other.

7.4. Pennsylvania and New Jersey

Card and Kruger studied minimum wage changes in New Jersey in 1992, and observed that unemployment did not get affected by this change. This is confirmed in Figure 4 because the unemployment rate actually declines after 1992.

In our paper, we consider New Jersey’s minimum wage change in 2014 and find that Card and Krueger’s findings are validated in this most recent change. Minimum wage does not increase the unemployment rate after 2014. Instead, we can see a decrease in overall unemployment after this change in 2014. This is significant with respect to differences in differences because Pennsylvania (without any changes to its minimum wage in 2014) did not see a sharp decline in its unemployment rate.

8. Regression Diff-in-Diff Estimation

We will do a differences in differences regression for each of the state-year pairs we are looking at. As this analysis is a replication of one done in Card and Krueger 1993, we will be examining the state-year interaction coefficient in our regression. The magnitude and significance of this coefficient will indicate (assuming that we have successfully controlled for all confounding factors) whether raising the minimum wage had a significant effect on unemployment in the state where it was raised as compared to the control state where it was not raised.

We will be including controls for:

- Race

- Education

- Sex

- Spoken English Proficiency

in order to eliminate the confounding caused by these third variables which are held by theory to have effects on employment.

8.1. Kentucky and Tennessee

We are looking at the 2010 wage change in Kentucky (from $6.55 to $7.25). In table 6, we see a few interesting results. First of all, it would appear from these states that raising the minimum wage results in a roughly 3% increase in youth employment. This effect disappears when looking at the full labor force.

This finding is consistent with the idea that the minimum wage will have a disproportionately large impact on youth unemployment, and will actually increase it by driving more young people into the workforce who previously were less inclined to do so because of low wages.

We should also note that there was a downwards trend in employment in 2010, due to the Great Recession, which appears in both of our coefficients for the year 2010, so our estimates do have some external validity in this respect.

8.2. Oregon and Washington

We are looking at the minimum wage change in Washington in 2001 (from $6.50 to $6.72). In Table 7, we notice for our regression both on youth unemployment and overall unemployment-that the State-Year Interaction term is significant. In youth unemployment, it has a positive magnitude, indicating that there was a 1.9% increase in employment in Washington from 2000 to 2001 which did not occur in Oregon. This indicates that raising the minimum wage in Washington actually led to a slight, but significant increase in youth employment. In the case of overall employment, we see that the minimum wage change in Washington actually led to a 0.6% decrease in employment.

This suggests that increasing the minimum wage led employers in Washington to turn away from older employees and towards more younger employees. The magnitudes of our coefficients align with this story and it makes sense that as more youth enter the labor force looking for jobs, they will displace older workers.

Additionally, we observe no significant differences between Washington and Oregon in youth unemployment, but there was a significant 1% decrease in youth employment from 2000 to 2001. That said, the full labor force had neither a significant difference between Oregon and Washington, nor between 2000 and 2001.

Finally, we observe that education, sex, and speaking English all have significant effects in the expected directions on employment in both the youth labor force and the full labor force. Race only has a significant effect in the youth labor market, while its effect is insignificant in the overall labor market.

8.3. Michigan and Ohio

Ohio increased its minimum wage from $7.95 to $8.10 in 2015. In table 8, we see that this change led to no significant interaction term, so while there were time-trend increases in employment going on at the time due to economic recovery from the Great Recession, there were no additional changes to employment due to raising the minimum wage.

We note that Ohio has a much higher employment rate in these years which is controlled for in this regression (and which we noted we had to look out for in the t-test section).

8.4. Pennsylvania and New Jersey

We are looking at the minimum wage change in New Jersey in 2014 (from $7.25 to $8.25). Looking at the coefficients in table 9, we see that the minimum wage increase had no significant effects on youth employment.

It did however lead to a .6% increase in full labor force employment, but this is a very small magnitude effect. We note that Pennsylvania has a much higher employment rate than New Jersey in both years and this is controlled for in our regression.

9. Conclusion

In general, our findings back up those of Krueger 2015. We find that between Michigan and Ohio as well as between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, a minimum wage increase has no significant effect of a meaningful magnitude on either youth or full employment.

We do however also find confirmation of one of the other trends identified in the literature. There is an extent to which raising the minimum wage leads to an increase in youth employment, offset by a decrease in adult employment. This is consistent with the idea that relatively affluent teenagers have high reservation wages, but are competitive workers when they enter the labor force in now-higher-paying minimum wage jobs.

The evidence from Oregon and Washington is most strong for this point. The additional effect of being in the state with the increase in minimum wage is an increase in youth employment of about 2-3% and a decrease in full labor force employment of about half a percent. Kentucky and Tennessee backs up the increase in youth employment, but doesn’t show the full labor force decrease.

Thus, based on the four minimum wage changes we analyzed, we do not find convincing evidence of the standard theory that raising the minimum wage must always lead to an increase in unemployment. The reality is much more nuanced. Firms do not have sufficient elasticity of labor demand to be able to change the number of employees they higher as a result of the increased cost of labor. Our research falls in line with the theory that higher costs of labor are passed on to the consumers.

The important policy result we do find is that a higher minimum wage drives more teenagers, who might otherwise not work, into the labor force. This makes the labor force more competitive and may lead to some reduction in employment of adults who need the jobs more (say because they are supporting a family). Further research in this area should try to better quantify the extent to which increases in youth employment are offset by decreases in adult employment.

However, the most important conclusion here is that the mantra “raising the minimum wage increases unemployment” should be retired because it is not consistent with empirical findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sylvia Klosin and Lindsey Currier for their guidance throughout the process of writing this paper. They would also like to acknowledge the members of OEconomica for their invaluable feedback on early drafts of this paper.

References

Allegretto, Sylvia, and Michael Reich. 2018. “Are local minimum wages absorbed by price increases? Estimates from internet-based restaurant menus.” ILR Review 71 (1): 35–63.

Betsey, Charles L, and Bruce H Dunson. 1981. “Federal minimum wage laws and the employment of minority youth.” The American Economic Review 71 (2): 379–384.

Card, David, and Alan B Krueger. 1993. “Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.”

Dube, Arindrajit, T William Lester, and Michael Reich. 2016. “Minimum wage shocks, employment flows, and labor market frictions.” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (3): 663–704.

Editorial Board, The. 2014. “The Case for a Higher Minimum Wage.” The New York Times.

Giuliano, Laura. 2013. “Minimum wage effects on employment, substitution, and the teenage labor supply: Evidence from personnel data.” Journal of Labor Economics 31 (1): 155–194.

Harasztosi, Péter, and Attila Lindner. 2015. “Who Pays for the minimum Wage?”

Krueger, Alan B. 2015. “The Minimum Wage: How Much Is Too Much?” The New York Times.

Lopresti, John W, and Kevin J Mumford. 2016. “Who Benefits from a Minimum Wage Increase?” ILR Review 69 (5): 1171–1190.

Romer, Christina D. 2013. “The business of the minimum wage.” The New York Times.

Wellek, Stefan. 2003. Testing Statistical Hypotheses of Equivalence. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

Appendix A: T-Test Tables

Appendix B: Time-Trend Figures

Below are plots of the unemployment rate in each state over time with vertical lines marking the years in which each state raised the minimum wage.

Appendix C: Regression Tables